Archive

-

Let the cataloguing commence!

Hi, it’s Gabrielle, Wilton’s Archive and Interpretation Manager here with exciting news - after much ‘behind the scenes’ preparation and planning we’re finally ready to make a start on cataloguing the Wilton’s Archive!

Read More -

-

A tankard embodying the true “spirit” of Wilton’s!

Since beginning work on cataloguing early this year my team of archive volunteers have been meticulously and systematically going through the boxes, listing their contents and making notes on all the interesting things they have found – from the obvious (such as production notes, progammes, and architect’s plans) to the unexpected.

Read More -

The Waste Land

Hello! I’m James, I’ve just joined Wilton’s as Archives and Interpretation Manager and have been burying myself amongst the 184 boxes that make up the beautifully rehoused Wilton’s archive.

Read More -

Wilton’s Luck

Wilton’s is certainly a lucky survivor, 150 years and still standing. Despite attempts by the Luftwaffe and the GLC slum clearances John Wilton’s music hall building has defiantly remained untouched. Unfortunately what does not remain are many records of the man himself, John Wilton sold the music hall in 1868 and none of his papers survive in our archive.

Read More -

A Tale of Two Churches

Music Halls have a notorious reputation for bawdy entertainments, though John Wilton was commended for running an ‘orderly house’ in a ‘notoriously difficult neighbourhood’. This did not stop Mr. and Mrs. Reginald Radcliffe and Miss Macpherson, passing in the mid-1880s, to be so shocked at what they saw on stage that they felt compelled to fall to their knees and pray ‘that God would break the power of the devil in the place’. It was soon after that the music hall closed and the buildings became the East End Mission, the Old Mahogany Bar.

Read More -

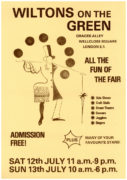

Wilton’s on the Green

Summer has arrived and everyone is eager to get Friday finished and enjoy the weekend sun. Today we look at the event Wilton’s on the Green.

Read More -

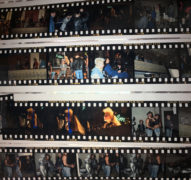

Shooting the Krays

Wilton’s has an illustrious legacy of live entertainment, however it was filmed productions by Spike Milligan that first brought the hall back into performance use and restored parts of the hall in the 1960s. Since then Wilton’s has appeared in numerous film, television and music video shoots. As a stalwart of the East End itself it is appropriate that Wilton’s played host to those other 1960s East End icons the Kray twins for the 1990 film The Krays starring Martin and Gary Kemp.

Read More -

Latest Acquisition

Wilton’s archive holds the treasures of our heritage; it ensures that our legacy is recorded by safeguarding our historic records and also by documenting Wilton’s today. Programmes, flyers, newsletters and press cuttings regularly enter the archive, as well as more unusual items. Our latest acquisition comes from the fantastic Hackney Colliery Band who played here 12-13th May 2016. The band’s performance has been recorded and filmed for a future live album; these EPs were given to audience members and we are very pleased to have number 451/1000 preserved in the Wilton’s archive.

Read More -

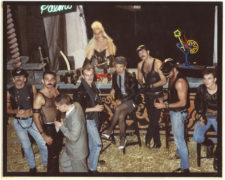

Frankie Goes to Wilton’s

Wilton’s has come full circle from music hall, to Methodist mission, to modern performance venue but during the depths of its dereliction it hosted a scene that would have scandalised even the Victorian sailors who frequented the more liberal balcony level of Wilton’s. In 1984 Frankie Goes to Hollywood shot in Wilton’s their staggeringly bold and controversial video for Relax.

Read More -

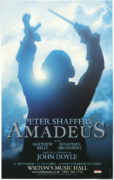

Amadeus: Requiem

In memory of Sir Peter Shaffer (1926-2016) this week we look back at our 2006 performance of his seminal work Amadeus. Originally opened at the National Theatre the Broadway transfer won the Tony for best play in 1981 and the film adaptation the best picture Oscar in 1985, not to mention best director, actor, costume, makeup among others; Wilton’s revival with Adam Spiegel Productions had a lot to live up to!

Read More -

A Softer Scaffolding

The East End Mission left Wilton’s in 1956, at which point the hall and houses had deteriorated beyond a sustainable point for continued community use. Alarmingly Britain lost 85% of its Theatres between 1914 and 1980, with most going between 1955 and 1976 (John Earl, British Theatres and Music Hall). Some were converted to Bingo halls, but the fate of Wilton’s echoed many whose large, cavernous auditoriums were valued not on aesthetics or heritage but on air volume. John Wilton’s hall became warehouse storage for a rag merchant.

Read More -

Restoration Mk. I

Wilton’s has won a RIBA National Award 2016 on top of its three London Awards. The final restoration has not only made the buildings structurally sound for the first time since its music hall days of the 19th Century, but is much loved by visitors as well as professionals.

Read More -

Wilton’s on the Move

The buildings of Wilton's have been on this site in one form or another since the 1690s. The hall itself is now the oldest surviving grand Victorian music hall, having been built in 1859. We all know that Wilton's survived the Blitz, the GLC slum clearances and decades of dereliction but despite this even those campaigning to save it had plans to pull it down!

Read More -

Memories of the Old Mahogany Bar Mission

A guest post from Archive Volunteer, Victoria Osborne

Read More -

Restoration Mk. II

The awards tally continues to grow; Wilton's recently won a NLA Award in the Conservation & Retrofit category!

Read More -

Mr Mason’s Memories

The Wilton’s archive is an incredible resource for uncovering our past, however the formal sequence only begins with the formation of a group to save Wilton’s from destruction in 1965. Materials pre-dating this have been generously donated in more recent decades. Arguably the most valuable resource is the living memory of those who played an important role in the history of Wilton’s.

Read More -

-

Acquisition: John Earl Papers

Wilton's archive is a rich resource, however like any collection there are holes. We are very pleased then that one of our leading stakeholders, John Earl has donated his papers to Wilton's.

Read More -

The Muppets

Music Hall was the populist entertainment of its day. In a way that film, television and now YouTube and social media have become. Wilton’s itself has met these new eras with notable appearances across film and television. One in particular stands out as particularly appropriate, in 2014 the Muppets came to Wilton’s.

Read More -

-

Wilton’s Launches Digital Archive

Wilton's Music Hall is proud to launch our digital archive in partnership with Google Arts and Culture, giving unprecedented access to Wilton's heritage through its collections and via a new virtual reality tour.

Read More -

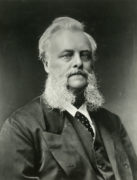

John Comes Home

One of the most precious and important objects in our collection is a photographic portrait of John Wilton himself. His dashingly mutton-chopped visage greets visitors in the John Wilton Room, our new permanent heritage space. As with many of our greatest treasures John’s portrait has not always been here at Wilton’s.

Read More -

FINDING FRANKIE

One of my favourite things about working in archives is discovering something unknown or recovering something long thought lost. You would be surprised at how often this happens, and a building as old as Wilton’s has all kinds of hidden corners and less visited areas.

Read More